The mid-90s was a race to get the world online. Every month, magazines such as PC Pro carried CDs from faceless ISPs desperate to bag sign-ups, but there was one ISP that was radically different from the rest, spearheaded by a man who was used to shifting millions of CDs of his own.

David Bowie didn’t just lend his name to an ISP; it wasn’t some half-arsed piece of merchandise. He regularly joined chats with members, and delivered internet innovations that were well ahead of their time, such as the live streaming of concerts and offering 3D environments for fans to mix in. All this long before YouTube or Second Life were even a thing.

We’ve spoken first-hand to the people who worked with Bowie to bring “cyberspace” to the masses. We’ll also hear from fans who gorged on unprecedented access to their hero.

If you’ve never thought of David Bowie as an internet pioneer, then we’re about to change your mind. This is the story of BowieNet.

Sound and vision

Table of Contents

Ron Roy had always been a music fan. “I had a Ziggy Stardust poster over my bed,” he said. “I was a massive Bowie fan. My cousins were members of the Monkees and the Beatles fan clubs. They would get stuff in the mail like a newsletter and would lose their minds.”

Roy and his business partner Bob Goodale forged successful careers in the entertainment industry and by the 1990s, believed “the net” could be the perfect medium to refresh the fan club model, but they needed a focus. “Bob knew Bill Zysblat [Bowie’s manager], so we decided to begin with David.”

Roy and Goodale secured a meeting with Zysblat and Bowie. “We still didn’t have all the dots connected, but we pitched for about three hours,” said Roy. Bowie loved the idea and concept. “We said we had to raise over a million dollars to get it going, to bring engineers and graphic designers in. Four or five days later, Zysblat called. ‘David wants in on the concept of the online fan club and he wants to be your first investor.’”

With Bowie’s backing, Roy and Goodale formed the technical partnership management company UltraStar, with a strategy to bring entertainment, sports and fashion clients to their “fan-club on the web” model. “We said, ‘let’s get this model, the technology, perfectly right. Let’s hyper focus on BowieNet, then bring more artists and bands to our platform and grow the company.”

BowieNet was conceived as Bill Clinton’s Telecommunications Act of 1996 became law. This marked a pivotal transition shift between the telephone and internet ages, and broke the monopoly of large telecommunication firms (such as AT&T) by distinguishing between telephony and data, allowing smaller companies to compete in building the “information superhighway”. Roy acknowledges this stroke of good fortune. “It allowed a white label model, any brand at that point could layer on the ISP,” he said. “Our timing was very lucky.”

The ISP chosen to power BowieNet was Concentric Network Corporation (now Verizon), but the in-house developers were skilled graduates from Carnegie Mellon and MIT. However, it was Bowie himself driving the innovation. “We didn’t want to overwhelm him with approving photos, graphics and navigation buttons, but he wanted to see everything,” said Roy. “David was a really good business partner and a great collaborator.”

UltraStarman

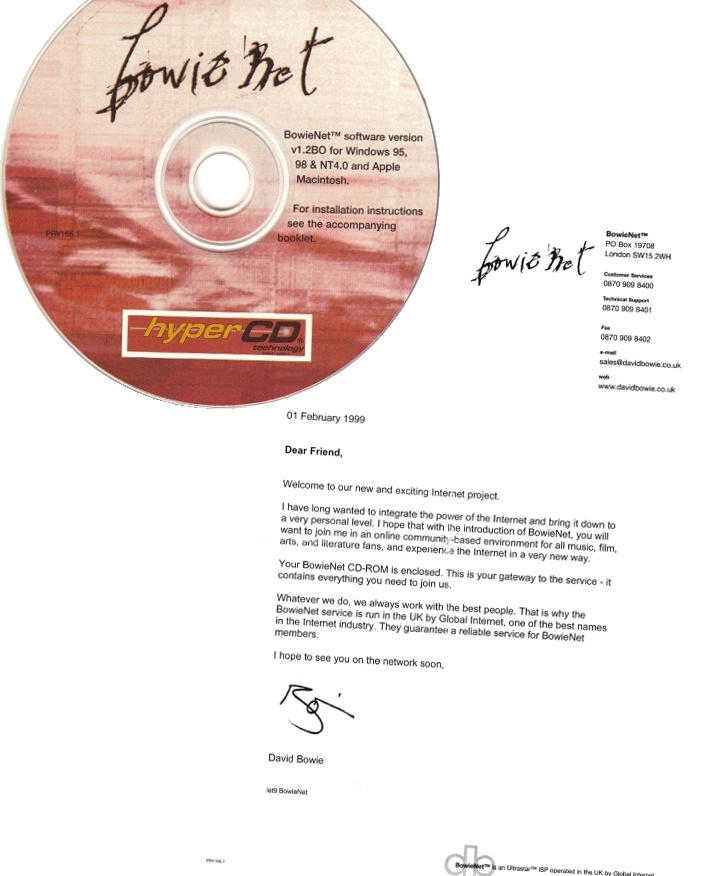

BowieNet launched in the USA on 1 September 1998, and was the showcase for UltraStar’s Affinity ISP. The concept was to give fans a direct gateway to their heroes. Nobody understood the importance of that exclusive access better than Bowie. He wasn’t just putting his name to the product; he was the product.

A monthly fee of $5.95 gave fans access to BowieNet, a subscription-only web service, but for $19.95 a month BowieNet also provided a dial-up internet service, complete with davidbowie.com email addresses and webspace to host Bowie fan sites. Irrespective of how fans accessed BowieNet, it offered a space for the like-minded to meet and socialise, years before MySpace, Friends Reunited or Bebo were launched.

Charlie Brookes discovered Bowie in the 80s, seeing him in concert almost 200 times. He was one of the first fans to join BowieNet. “I didn’t hesitate,” she said. “It had David Bowie attached to it, so I was interested.”

One BowieNet innovation that hooked Brookes was BowieWorld, a 3D environment for fans to meet which predated Second Life by half a decade. “There were 12 rooms and you became a 3D avatar, not just a name on a screen,” she recalls. “It was a proper interactive thing. You could go in and dance with your mates. I used BowieWorld to chat with my mates in America and all over Europe.”

BowieWorld was developed by Worlds and, because of the immense hardware requirements to run the application software, it ran on their hardware, not UltraStar’s. “Thank God,” laughs Ron Roy. “That was way beyond our technical scope, but David created his own avatar to be in there.”

Another innovation of BowieWorld was gamification. “Initially you were a penguin and it took months of interaction to build your character, then you became a human and could choose clothes and stuff like that,” said Brookes.

Brookes’ penguin avatar became one of the many subjects of conversation when she was picked to chat with David Bowie on a Talk Radio/BowieNet “simulcast” in January 1999. Bowie said: “Charlie, I know exactly why you like it so much. I really love going in the chat room, so I go in both as myself and anonymously.” It’s an open secret that Bowie’s username was Sailor, but he confessed to Brookes about an alternative sobriquet. “I’ve been frequently in as Mr Plod. When you go in as David Bowie, they don’t believe it’s you.”

BowieNet member Steph Lynch was wowed by Bowie’s keenness to engage. “He was incredibly curious and liked to share his knowledge and passion,” she said. “He genuinely was interested in people and what they found interesting and exciting. You could have conversations, debates, discussions and also be incredibly silly.”

Lynch devised a technical solution to notify her whenever Bowie appeared on BowieNet. “I’d leave my computer running and every 57 minutes it would disconnect from the internet and redial, so I learned to go to sleep with my modem making noises. It was configured so that when Sailor appeared, a loud noise would play.” This was, of course, in the dial-up days when every minute spent online was added to your phone bill.

Still, the heinous expense of maintaining a round-the-clock internet connection paid off when Lynch first met Bowie. “He knew who I was,” she said. After a London TV appearance, Lynch had met up with other BowieNet fans. “I made a crap website with photographs from that evening and he must have gone through them because it’s the only way he would have been able to put my name to my face.”

Remember, in the 1990s, Lynch couldn’t post phone pics to Instagram. She had to get the film developed, scan the images, create thumbnails then throw everything together with HTML. “I didn’t do it for him,” she said. “I did it because everyone wanted copies. People had come from all over the place to see David. That sense of community added an extra dimension.”

Stream like a baby

BowieNet succeeded in connecting Bowie with his fans, but his music always took centre stage. Although BowieNet Radio played curated tracks a decade before Spotify appeared, it was the streaming of performances that were the real fan highlight. In the 90s, it was technologically risky, as Roy explains. “David was up for something that may not [have worked] because a 56k modem was so limited. We tried every compression algorithm people would bring to us. We could record and compress concerts, then put up snippets, but when we did live streams, we’re always sitting there saying, ‘please technology gods, be nice to us’.”

That pressure was also felt on stage. Mark Plati is a musician and songwriter, co-producing two Bowie albums (Earthling and Heathen) from the BowieNet era. “The first cybercast was 30 September 1997,” he said. “We went to Boston and did a show. I had to sit at a little desk with headphones and mix it, basically like it was going out on the radio, except that there was no radio, it was going out on the web live. That was not only the first time I’d ever done it, but the first time I’d ever considered it was a possibility.”

Plati played on and produced Bowie’s 1996 track “Telling Lies”, which is considered the first downloadable single by a major artist. He also played on “What’s Really Happening?”, a track where writing the lyrics was a BowieNet competition prize. Plati understands why Bowie threw himself into BowieNet. “I wasn’t surprised because he would put that energy in everything,” he said. “He’d go 200%, not a shock at all. And it was cool.”

Bowie was keen to share his passion for the internet with other members of his band. Singer, songwriter and musician Emm Gryner appears on several of Bowie’s live albums. “I had a website of my own and I remember him giving advice on how to do it. ‘You’ve got to click through like you’re the fan and experience it’. I remember him being really excited about the opportunities and connectivity that it brought.”

Gryner also recalls seeing the BowieNet fans from the stage. “You could see the neon green shirts of BowieNet members, show after show. It was a reminder that innovation was happening behind the scenes. I think David took pleasure in showing what could be done. The end of it always was about how can we connect, not how to make a zillion dollars.”

Gryner, Plati and Bowie shared a stage many times. In 2000, they performed to 250,000 people at Glastonbury and again, two days later, at the BBC Theatre in London for only 250 invited BowieNet fans. Gryner remembers that the performances for BowieNet fans felt different. “I remember being at the BBC Theatre playing “Heroes” and David saying that it felt too big for the venue. I don’t know if that speaks to anything about the BowieNet community being so small, but they were so into it. That was something that stood out to me about how he felt about that show.”

Mark Plati also noticed David’s connection with BowieNet members. “He was so committed. We did Wembley [NetAid, 9 October 1999] and then went to Ireland for 200 people. I’m sure they viewed it as cutting edge, having BowieNet as this way to connect, but his fans had already found a way to do that. This just made it super-efficient.”

Ch-ch-ch-ch-changes

By the new millennium, BowieNet was running in the USA, UK and Europe. “You had to figure out the billing, exchange rates,” laughs Roy. “We had customer service, where it’s 3.13 here and 8.13 there, so lot of emails and lots of taking care of people.”

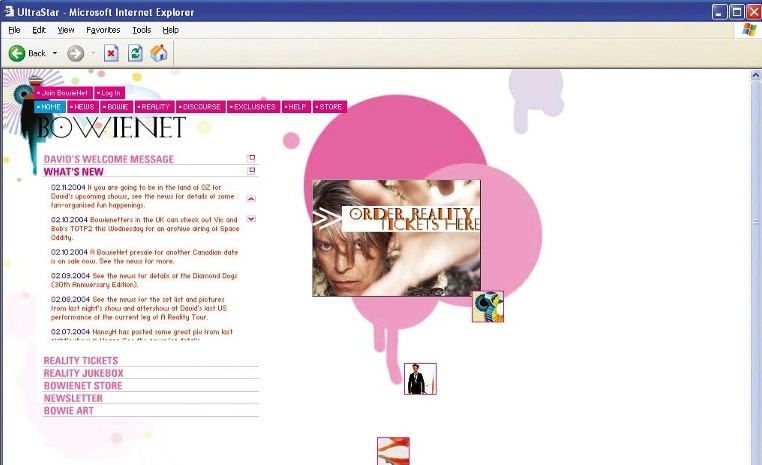

With broadband set to increase the operational complexity, UltraStar got out of the ISP business, ushering users to the $5.95 (or equivalent) subscription for BowieNet. It was a good move. “Very few customers left the platform,” said Roy. “We were pleasantly surprised, it showed the strength of the affinity.”

Seeing what BowieNet had achieved compelled other major music acts to sign up to UltraStar’s offering, but Steph Lynch believes that there’s a reason we’re not talking about HansonNet or RedHotChilliPeppersNet. “It wasn’t a bunch of media managers making decisions. David was the driving force behind it.”

For what would become Bowie’s final tour (A Reality Tour), BowieNet subscribers enjoyed videos of rehearsals, invites to BowieNet-only gigs, tour bus footage and priority ticket access. Bowie and UltraStar also continued to push technological boundaries. A performance from London’s Riverside Studios in September 2003 was broadcast on BowieNet and to cinemas around the globe in 5.1 surround sound.

Sadly, however, it all came to a rather abrupt end. The Reality Tour halted in June 2004 when David Bowie suffered a heart attack during a show. Save for one or two appearances, Bowie all but vanished from public life. The fuel for BowieNet was gone. “It was a ten-year journey,” said Roy proudly. “David was stepping away, he had some health issues and was really focused on raising his daughter. The partners got together and said it was time to wind this down.”

UltraStar was sold to Live Nation and BowieNet became a free-to-all website. Without the affinity hub, the fans scattered. “It’s just the way the internet went,” said Charlie Brookes. “Everything changed with social media. You don’t need to go [to BowieNet] because it’s all over Facebook and, of course, he wasn’t there to drive the car.”

Yet, even though the BowieNet hub was long since dissolved, a community remains. “We still get together and it’s as though nothing has changed,” said Lynch. “A few years ago we met and it was like a mini BowieNet reunion.”

Plati suggests BowieNet provided an environment that’s hard to replicate on social media. “There were no trolls on BowieNet. It was a community that you wanted to belong to and you had to pay to be part of. Facebook is free and you get all kinds of whatever on there. I wouldn’t find that very exciting.”

Having become great friends with Bowie, Emm Gryner wonders how he would have felt about social media. “There was something about that insider community that changed with social media. If I’m going to put something out on socials, the whole world can comment. That doesn’t seem to me like something that would have particularly excited him.”

No, what excited Bowie wasn’t only the pioneering live streams, the 3D environments or unique downloadables, but the opportunity to interact in a shared safe space with his most loyal fans. As Ron Roy put it: “The connectivity was great, the affinity was greater.”